Earlier this year, Code for Science & Society convened scientists, community organizers, and technologists to co-design a “Climate-Sensitive Infectious Disease” (CSID) Open Source Software Community of Practice. This gathering was part of a broader project to understand the existing landscape of community groups and projects working on open source software related to climate-sensitive infectious diseases. We organized the gathering to catalyze new relationships and to determine whether and how a transnational, transdisciplinary community of practice could be useful for those working on CSID tools.

On the first day of the program, we wanted to build new relationships and set the context for discussion including a sense of who was in the room and the expertise they brought. Forty-five participants, from over 18 countries, representing university research projects, nonprofit organizations, and technology organizations gathered in Cape Town.

The conversation opened by establishing Community Agreements. The initial uncertainty was broken when someone bravely spoke up: “I’ve never done this before and I bet most academics here in the room haven’t either.” The conversation then quickly moved from “this is weird” to “how about this!” and then “here’s something important.” This exercise encouraged participants to have agency over their own space and community and raised issues of equity and horizontalization.

A “fishbowl” session was hosted where a dynamic, changing circle on the inside had an organic conversation that was being actively watched and listened to, and at times interjected, by an outer circle of participants. This activity offered participants a sense of why we were all in the room and the different backgrounds and areas of expertise that everyone brought.

The conversation opened with a discussion on software sustainability. The founder of ROpenSci mentioned that documentation of best practices for software development have significantly improved in the past 10 years. Thus, he suggested it was more salient to begin with confirming first that there is an appropriate demand and interest in the product rather than beginning from a question of longevity and sustainability.

Others joined the circle and the conversation turned to questions of data access and ethical data practices. If a model is only as good as its data, how do you ensure you are accessing good data? One member of the group mentioned that there are several examples of opening up data that have gone badly. Data access, she emphasized, is fundamentally about relationships. That is also how you enable your models to be used. She underlined that it is important to consider why models are needed in the first place, to what purpose will the data be used, and how to close the feedback loop to enable communication thereafter. Data needs to be procured in a way that is respectful to the original terms of data collection in the field and understood within its context and the individuals it represents, rather than solely focusing on it as numbers and statistics.

A question was raised, if data is based on social relations, how can new entrants – such as small organizations or young Primary Investigators – be supported to have access that is equitable and enables them to participate? This was answered as being about building processes that enable those who have access to support newcomers to also gain access.

A new voice joined the conversation and reiterated the importance of getting feedback early and understanding the needs of the specific community for whom a software product is being developed. They made the distinction between the client (the actual user or decision-maker) and the ultimate beneficiary (the general public) and explained that targeting the right client is crucial, especially in cases where there may be a subscription model or financial considerations. They mentioned that decision-making power may lie with planning and finance departments rather than the line ministry responsible for a specific domain, so it is important to understand the decision-making dynamics within government and find the right individual champions who understand the issue and can influence resource allocation within the government.

The conversation turned to the imbalance between the abundance of data in some parts of the world and the lack of data in others, making it challenging to build robust models. A climate scientist added to the conversation noting that contrary to popular perceptions about climate data as not having ethical issues, climate scientists, like public health scientists, face complexities when working with different types of data, including biases and limitations that need to be carefully considered. A software engineer noted that metadata, or data about the data, and context building are crucial for understanding and utilizing datasets effectively. Synthetic data and geospatial data were raised as possible useful alternatives when original data is limited or inaccessible.

An open data expert raised the importance of establishing feedback loops in data systems, specifically illustrated through the example of the DHIS (District Health Information Service) in Bangladesh. Despite the system being widely used and collecting data at the facility level, there were instances where the data did not make its way back to inform decision-making and service delivery. Encouraging the flow of data back to the individuals and communities it pertains to requires intentional efforts and can be achieved through operational practices outside of policy.

The fishbowl activity was an embodied way to practice the kinds of advice and conversations a supportive community of practice might be able to provide. People practiced self-management during the fishbowl, leaving the circle and making space for others without having to be asked to; always leaving an open seat; not hogging the mic, etc.

The afternoon of Day 1 closed with a grounding presentation by Code for Science & Society Director of Programs, Dr. Angela Okune who laid out some of the reasons for the gathering and the work ahead. Ample time was given for groups to rest and recoup before an evening dinner and show at Gold Restaurant.

Day 2 leveraged the relationships and conversations built on Day 1 as a springboard for deepening conversation about the ideal design for a CSID community of practice. We began with a World Café session where participants sat at different tables to answer the following prompts:

What difference will having the various people we discussed be involved make?

What activities can connect these different people together? What or who will this impact and why do we want that?

What’s out-of-scope for this CoP? What are its bounds that guard and define what it will focus on?

One person anchored the conversation and remained at the table while others scattered around the room for each question. Through these conversations, we collectively surfaced the elements of the CoP design, namely the who, what, and why.

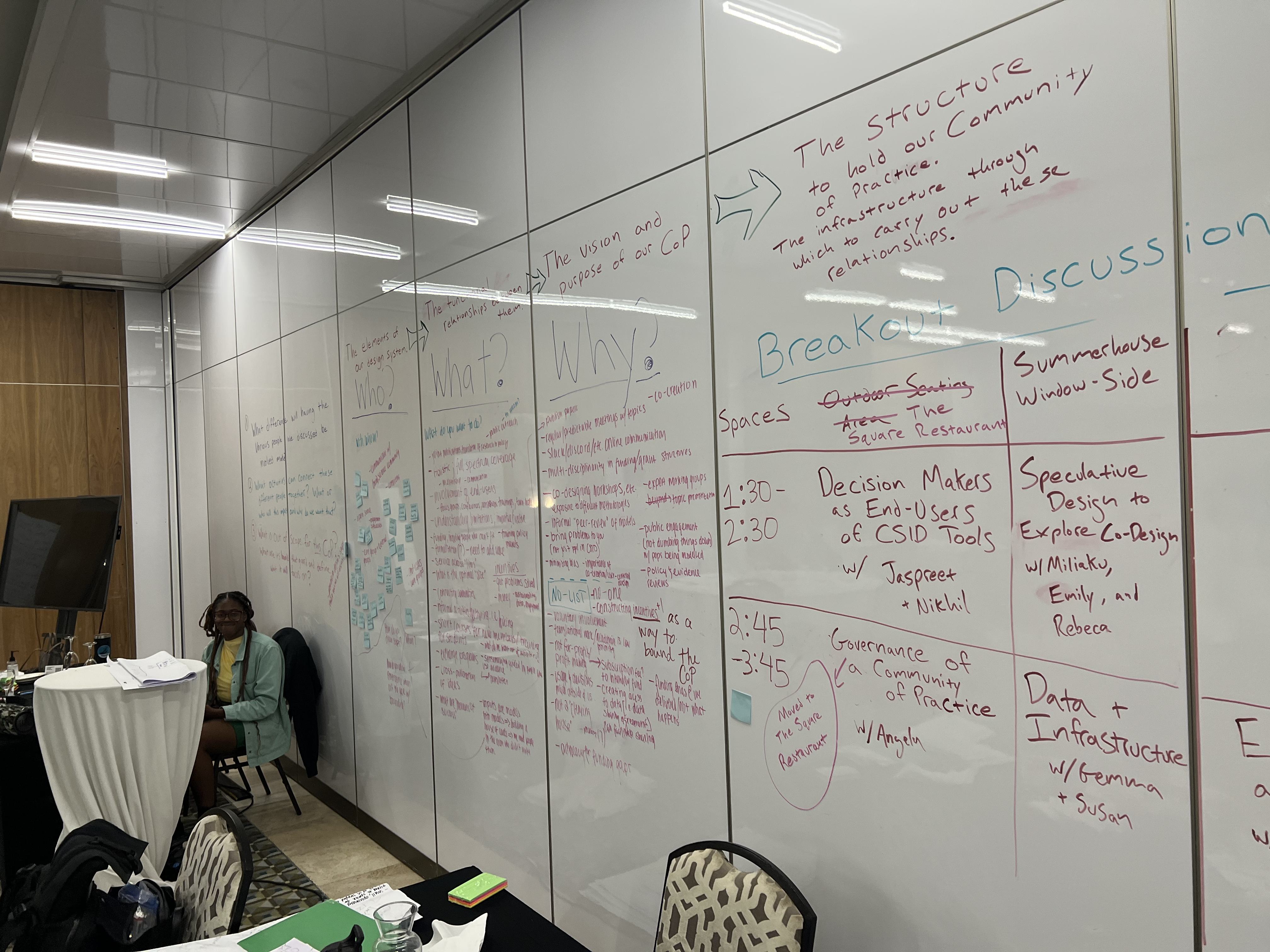

Following lunch, emergent breakout conversations were scheduled. These breakout groups covered topics such as “Decision Makers as End-Users of CSID Tools” and “Modeling Uncertainty and Interfaces between Climate and Epidemiological Models.”

Following the breakout discussions, groups reported back and virtual participants from teams who could not attend were invited to listen in.

We closed Day 2 with a happy hour event in downtown Cape Town to connect CSID workshop participants and also draw in new and old collaborators and partners working in open science, open source and research software, social justice, and related fields in Cape Town.

Our final day together sought to sketch out an articulation of what work participants may want to start moving forward on. We articulated what specific activities the CoP would start with and who and when such activities should begin.

These activities are represented in the full report, which will be launched here on our blog shortly. We closed our time together cultivating joy and engagement as a community.

We are excited to share the full landscape report soon, which includes detailed emergent themes from landscaping of the CSID field and desired future activities for the continuation of this community!

Featured image caption: The CSID Co-Design Workshop took place at the foot of Table Mountain in Cape Town, South Africa. Photo by Angela Okune.

![O:28:"craft\elements\db\AssetQuery":96:{s:27:"�yii\base\Component�_events";a:0:{}s:35:"�yii\base\Component�_eventWildcards";a:0:{}s:30:"�yii\base\Component�_behaviors";a:1:{s:12:"customFields";O:35:"craft\behaviors\CustomFieldBehavior":112:{s:5:"owner";r:1;s:34:"�yii\base\Behavior�_attachedEvents";a:0:{}s:10:"hasMethods";b:1;s:16:"canSetProperties";b:1;s:15:"personFirstName";N;s:14:"personLastName";N;s:5:"image";N;s:11:"personTitle";N;s:14:"contentBuilder";N;s:4:"text";N;s:11:"attribution";N;s:6:"people";N;s:10:"groupTitle";N;s:13:"relatedPeople";N;s:15:"relatedProjects";N;s:11:"relatedNews";N;s:8:"heroText";N;s:6:"teaser";N;s:13:"featuredImage";N;s:11:"postContent";N;s:6:"alumni";N;s:4:"logo";N;s:7:"website";N;s:11:"affiliation";N;s:7:"project";N;s:15:"applicationLink";N;s:16:"shortDescription";N;s:19:"applicationDeadline";N;s:10:"employment";N;s:15:"nonprofitStatus";N;s:13:"callsToAction";N;s:11:"description";N;s:7:"endDate";N;s:7:"endTime";N;s:14:"relatedProgram";N;s:9:"startDate";N;s:9:"startTime";N;s:8:"ctaTitle";N;s:7:"ctaLink";N;s:14:"ctaDescription";N;s:8:"timeZone";N;s:4:"tags";N;s:7:"context";N;s:11:"peopleGroup";N;s:9:"groupName";N;s:5:"users";N;s:4:"body";N;s:6:"header";N;s:7:"buttons";N;s:10:"buttonLink";N;s:5:"style";N;s:14:"quickLinkItems";N;s:8:"itemLink";N;s:15:"quickLinksTitle";N;s:17:"quickLinksDisplay";N;s:10:"visibility";N;s:9:"linkField";N;s:13:"featuredEvent";N;s:12:"featuredPost";N;s:12:"contributors";N;s:11:"grantAmount";N;s:8:"richText";N;s:3:"bio";N;s:4:"news";N;s:8:"projects";N;s:4:"jobs";N;s:6:"events";N;s:9:"resources";N;s:7:"caption";N;s:14:"mailingAddress";N;s:7:"twitter";N;s:12:"contactEmail";N;s:3:"ein";N;s:7:"userOrg";N;s:9:"loginText";N;s:8:"grantees";N;s:10:"fileGroups";N;s:18:"sectionDescription";N;s:12:"sectionTitle";N;s:5:"files";N;s:5:"width";N;s:12:"resourceType";N;s:12:"accessDenied";N;s:8:"noAccess";N;s:8:"linkedin";N;s:6:"github";N;s:17:"incubatorProjects";N;s:9:"listItems";N;s:14:"sectionContent";N;s:13:"headerContent";N;s:4:"year";N;s:13:"passwordReset";N;s:19:"restrictedResources";N;s:11:"headerStyle";N;s:5:"embed";N;s:14:"seoDescription";N;s:8:"seoImage";N;s:14:"analyticsEmbed";N;s:17:"programLogoSquare";N;s:19:"newsletterEmbedCode";N;s:11:"seoSettings";N;s:9:"shareLink";N;s:12:"feedbackLink";N;s:15:"feedbackFormUrl";N;s:26:"resourceFeedbackButtonText";N;s:16:"noUpcomingEvents";N;s:14:"personPronouns";N;s:17:"expiredJobWarning";N;s:10:"eventStart";N;s:8:"eventEnd";N;s:11:"maintainers";N;s:55:"�craft\behaviors\CustomFieldBehavior�_customFieldValues";a:0:{}}}s:6:"select";a:1:{s:2:"**";s:2:"**";}s:12:"selectOption";N;s:8:"distinct";b:0;s:4:"from";N;s:7:"groupBy";N;s:4:"join";a:1:{i:0;a:3:{i:0;s:10:"INNER JOIN";i:1;a:1:{s:9:"relations";s:14:"{{%relations}}";}i:2;a:4:{i:0;s:3:"and";i:1;s:40:"[[relations.targetId]] = [[elements.id]]";i:2;a:2:{s:18:"relations.sourceId";i:860;s:17:"relations.fieldId";i:3;}i:3;a:3:{i:0;s:2:"or";i:1;a:1:{s:22:"relations.sourceSiteId";N;}i:2;a:1:{s:22:"relations.sourceSiteId";i:1;}}}}}s:6:"having";N;s:5:"union";N;s:11:"withQueries";N;s:6:"params";a:0:{}s:18:"queryCacheDuration";N;s:20:"queryCacheDependency";N;s:5:"where";N;s:5:"limit";N;s:6:"offset";N;s:7:"orderBy";a:1:{s:19:"relations.sortOrder";i:4;}s:7:"indexBy";N;s:16:"emulateExecution";b:0;s:11:"elementType";s:20:"craft\elements\Asset";s:5:"query";N;s:8:"subQuery";N;s:12:"contentTable";s:12:"{{%content}}";s:12:"customFields";N;s:9:"inReverse";b:0;s:7:"asArray";b:0;s:18:"ignorePlaceholders";b:0;s:6:"drafts";b:0;s:17:"provisionalDrafts";b:0;s:7:"draftId";N;s:7:"draftOf";N;s:12:"draftCreator";N;s:15:"savedDraftsOnly";b:0;s:9:"revisions";b:0;s:10:"revisionId";N;s:10:"revisionOf";N;s:15:"revisionCreator";N;s:2:"id";N;s:3:"uid";N;s:14:"siteSettingsId";N;s:10:"fixedOrder";b:0;s:6:"status";a:1:{i:0;s:7:"enabled";}s:8:"archived";b:0;s:7:"trashed";b:0;s:11:"dateCreated";N;s:11:"dateUpdated";N;s:6:"siteId";i:1;s:6:"unique";b:0;s:11:"preferSites";N;s:6:"leaves";b:0;s:9:"relatedTo";N;s:5:"title";N;s:4:"slug";N;s:3:"uri";N;s:6:"search";N;s:3:"ref";N;s:4:"with";N;s:13:"withStructure";N;s:11:"structureId";N;s:5:"level";N;s:14:"hasDescendants";N;s:10:"ancestorOf";N;s:12:"ancestorDist";N;s:12:"descendantOf";N;s:14:"descendantDist";N;s:9:"siblingOf";N;s:13:"prevSiblingOf";N;s:13:"nextSiblingOf";N;s:16:"positionedBefore";N;s:15:"positionedAfter";N;s:17:"�*�defaultOrderBy";a:1:{s:20:"elements.dateCreated";i:3;}s:53:"�craft\elements\db\ElementQuery�_placeholderCondition";N;s:51:"�craft\elements\db\ElementQuery�_placeholderSiteIds";N;s:39:"�craft\elements\db\ElementQuery�_result";N;s:47:"�craft\elements\db\ElementQuery�_resultCriteria";N;s:46:"�craft\elements\db\ElementQuery�_searchResults";N;s:42:"�craft\elements\db\ElementQuery�_cacheTags";N;s:42:"�craft\elements\db\ElementQuery�_columnMap";a:0:{}s:51:"�craft\elements\db\ElementQuery�_joinedElementTable";b:0;s:8:"editable";N;s:7:"savable";N;s:8:"volumeId";N;s:8:"folderId";N;s:10:"uploaderId";N;s:8:"filename";N;s:4:"kind";N;s:6:"hasAlt";b:1;s:5:"width";N;s:6:"height";N;s:4:"size";N;s:12:"dateModified";N;s:17:"includeSubfolders";b:0;s:10:"folderPath";N;s:14:"withTransforms";N;}](https://images.codeforsociety.org/production/images/People/Angela-Okune-bio-photo.jpeg?w=360&h=360&auto=compress%2Cformat&fit=crop&dm=1671227256&s=90cfc0c695f5ff0486c2a6df0c070cc9)